|

History of Portmahomack Harbour |

|

Fishing and Trade Fishing, not surprisingly, has taken place in Portmahomack since the first human settlements, with evidence from shell heaps from the 14th Century found during the Archaeological excavations of 1994, just south of the Discovery Centre (1). Portmahomack’s sheltered bay was one of the few natural safe ports on the north east coast, and early mariners used the beach for launching their craft The history of the harbour is inextricably linked to fishing, coal, grain and potatoes Shell heaps (mainly muscles), and Cod bones dating from 1670, and Cod and Skate bones dating from 1700, reveal the principle catch of those times. Ling, Halibut and Turbot were plentiful, but by 1750, Cod numbers were reducing. Lobsters peaked around 1792, with 40,000 caught between March and July of that year. In 1839 there were 112 vessels exporting local grain to London, Leith, and Liverpool.

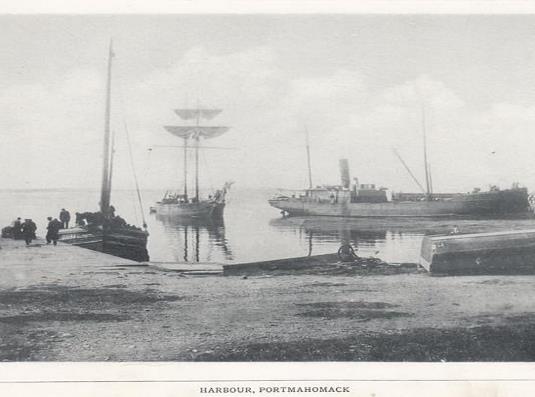

The Herring Boom 1850 to about 1890 was a prosperous era for Portmahomack, with Harbour buildings, Ice houses and cottages being built. The population doubled during peak fishing season, with labour coming from all over the Highlands. Until 1864, a maximum of 20 herring boats could be accommodated, increasing to 60 following harbour improvements funded privately by Cadboll of Hilton (see later). Following these improvements, 120 vessels were landing mainly Herring, in addition to Haddock, Cod, and Salmon. 46 of those boats were operated by 135 local fishermen. Much of the Herring was exported to Ireland. The main imports were Coal and Salt, and exports were mainly grain, potatoes, and herring. Because of severe overcrowding of the harbour, 15,000 barrels of herring, 1,600 barrels of haddock, and 240 barrels of cod had to be carried overland to the Cromarty ferry at Nigg. It was possible, at that time to walk from the harbour, across to the slipway, over the decks of the boats Involved in harbour activity at that time were 135 local fishermen with 46 boats, and 522 ancillaries, including, coopers, venders, gutters, packers, bait carters, curers, and net menders. The harbour was seriously overcrowded, and because it was unusable at low tide, required frequent dredging. Fishing boats could not get into the harbour to land their catch, often resulting in deterioration and loss of fish. By the 1890s, Herring catch was in decline, mainly due to the emergence and proliferation of the steam trawlers from 1885 (which were subsequently banned from entering the Firth). The building of Balintore harbour two years later, resulted in further decline in the harbour use, and subsequently, local employment and prosperity. By 1935, coal imports and grain exports were also coming to an end Salmon fishing was able to continue and thrive from the 1850’s, as these boats (cobles) had shallow draughts, allowing them to use the harbour, even at lower tides. Salmon fishing was not allowed on Sundays, and the leaders (net structure designed to channel the Salmon into the main ‘bag net’) had to be taken ashore until Monday! But by the late 20th century, this also went into serious decline, and, a few years ago, had ceased altogether. Haddock, once plentiful, are also now very scarce. Cod has now followed this worrying trend, with Crustacean fishing now being the major commercial operation, although now there are only a handful of commercial boats operating from Portmahomack. The main fish caught by leisure fishermen these days are Mackerel, Cod (which now must not be landed), Rock Cod, Pollock and Ling. Lobster numbers also now appear to be in decline.

The Telford Harbour Our harbour has had a chequered past, with many of the themes and problems still relevant to this day. It is classed as a Grade B Listed ‘Building’, such that any changes must pass a vigorous examination and approval process. The harbour area, along with most of the Main Street, is a Conservation Area. The first recorded structure was a basic pier, funded in 1698 by Viscount Tarbat, having realised that the beach would be inadequate for accommodating the larger boats needed to export local grain to Leith. However, due to inadequate maintenance, by 1786, the 88 years old pier was in ruins, leaving the 10 fishing boats and 2 Freight boats that used it, without shelter. Thomas Telford reported in 1790, that Wick and Portmahomack were the only two locations north of Cromarty, suitable to build a safe, sheltered harbour (see appendix 1). Because of problems raising the necessary funds (a recurring theme to this day!), it wasn’t until 16 years later, in 1816, that the harbour was completed. The final cost was £3168. This original Telford designed harbour measured 350’ in length, with a 70’ ‘return pier’ (the L shaped bit at the end!). In November 1826 a violent storm resulted in the loss of 16 vessels, and Robert Stevenson was commissioned to design and construct a lighthouse at Tarbatness. This cost £3732 and was completed in 1830. Originally white, the red bands were added in 1915 By 1828, only 12 years since completion, Portmahomack Harbour had become very dilapidated, having had little maintenance, and was badly damaged by the storm, 2 years earlier. Robert Stevenson was thus commissioned in 1853, to survey and recommend the required repairs. He also advised that the prevailing North Easterly storms would deposit sand and shingle around the end of the harbour (which proved to be correct). He therefore advised (as did Telford, 63 years earlier) that a stone breakwater (or ‘landbreast’) should be constructed at the North East end of the pier, but this was never done. Again, funding was not to be forthcoming, and in 1857, some 5 years later, only limited improvements were carried out, at a cost of only £80. In 1863, at the height of the ‘Herring boom’, Macleod of Cadboll became the owner of the harbour, on condition that he would spend £1000 on the necessary improvements. He commissioned the Slipway (known to locals simply as the ‘Slippy’), to make it easier for the herring boats to unload. He funded the badly needed dredging, as the harbour remained, as always, totally inadequate for larger ships. Ships had to lie off and wait for spring tides before they could enter the harbour, often with subsequent deterioration and loss of the fishermens’ catch. Cadboll’s improvements, based on Stevenson’s earlier report, increased the number of useable berths from 20 to 60, and the harbour, at that time, became the main fishing port for Inver, Rockfield, and the Seaboard villages. 1892 saw the building of Balintore harbour, and as a result, Portmahomack suffered further decline, due to the harbour’s natural inadequacies of access by larger vessels. The pier at Rockfield had been built in 1829, but proved to be quite unsuitable, due to the exposed location. Over the subsequent few years, Finlay Munro, as secretary of the Harbour Committee, campaigned for improvements, again including deepening and lengthening of the harbour, to allow larger vessels to enter, and increase the available number of berths. He pointed out that very little had been spent on maintenance in 100 years, other than building the slipway, which was considered to be ‘of little use’. The harbour had been in private ownership (Cadboll trustees) for 30 years and, predictably, the £4000 needed for improvements could not be found, as Balintore was now considered to be the main port of the Tarbat peninsula. In 1918, Portmahomack Harbour Trust took over the ownership from the Cadboll Trustees, and the harbour was regularly dredged between the wars. Coal and agricultural products continued to be imported, and potatoes and grain were exported, until 1935. Grenair (a private company) assumed ownership for a few years, before being adopted by Highland Harbours (Highland Council) in the early 1980’s. Ladders, lighting, replacement of the edging boards, and resurfacing all followed, along with occasional dredging. In the last 60 years or more, only a handful of commercial boats have fished from the harbour, with Salmon, Crab and Lobster being the main catch. With increasing prosperity, leisure time, and tourism, private leisure boats have increasingly made use of the harbour. However, because of increasing regulation, health and safety issues, etc., there were only 7 usable berths left along the harbour wall, several of which could only be accessed for an hour or two each side of high water. In 2006, thanks to the efforts mainly of local man, Kenny Aiken, a pontoon was built between the Harbour and the Slippy, creating an extra 14 berths, making 21 in total, (almost taking us back to the number available before the improvements of 1862! ) A major storm in 2013, severely damaged the harbour parapet, with a repair bill of £400,000, funded jointly by Highland Council and Central Government. Since then, repointing and further repair work has been required to the back of the harbour. Perhaps all of this might have been avoided had Telford and Stevenson’s suggested landbreast / breakwater been funded? The ongoing problems of dredging, lack of berths (there are 25 on the waiting list for berths at the last count), and maintenance of the 200 years old harbour, are therefore, painfully familiar. If the harbour is to survive, both as a well-loved, historic monument, and for the pleasure of future generations, it will require ongoing care and attention from its’ owners, driven by local and motivated people, who, as always, will need to continually fight for the necessary funding and investment.

Acknowledgments Carver, (2008); Portmahomack; Monastery of the Picts Fraser and Munro, (1988): Tarbat, Easter Ross: A Historical Sketch Both these books are currently available on Amazon, but in very limited quantities. The following website also contains further local historical information from Carver et al. http://books.socantscot.org/digital-books/catalog/book/4 Should you wish to further explore the fascinating history of the village, a visit to the Tarbat Discovery Centre, is highly recommended. It is an internationally renowned centre of our Pictish history with some fascinating artefacts on display. There are also many old photographs of the harbour, the village, and its’ residents, during the Herring boom of the mid 19th century. |